What Senior Leaders and Junior Team Members Get Wrong About Contribution

31. “Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs got it wrong” - Simon Sinek

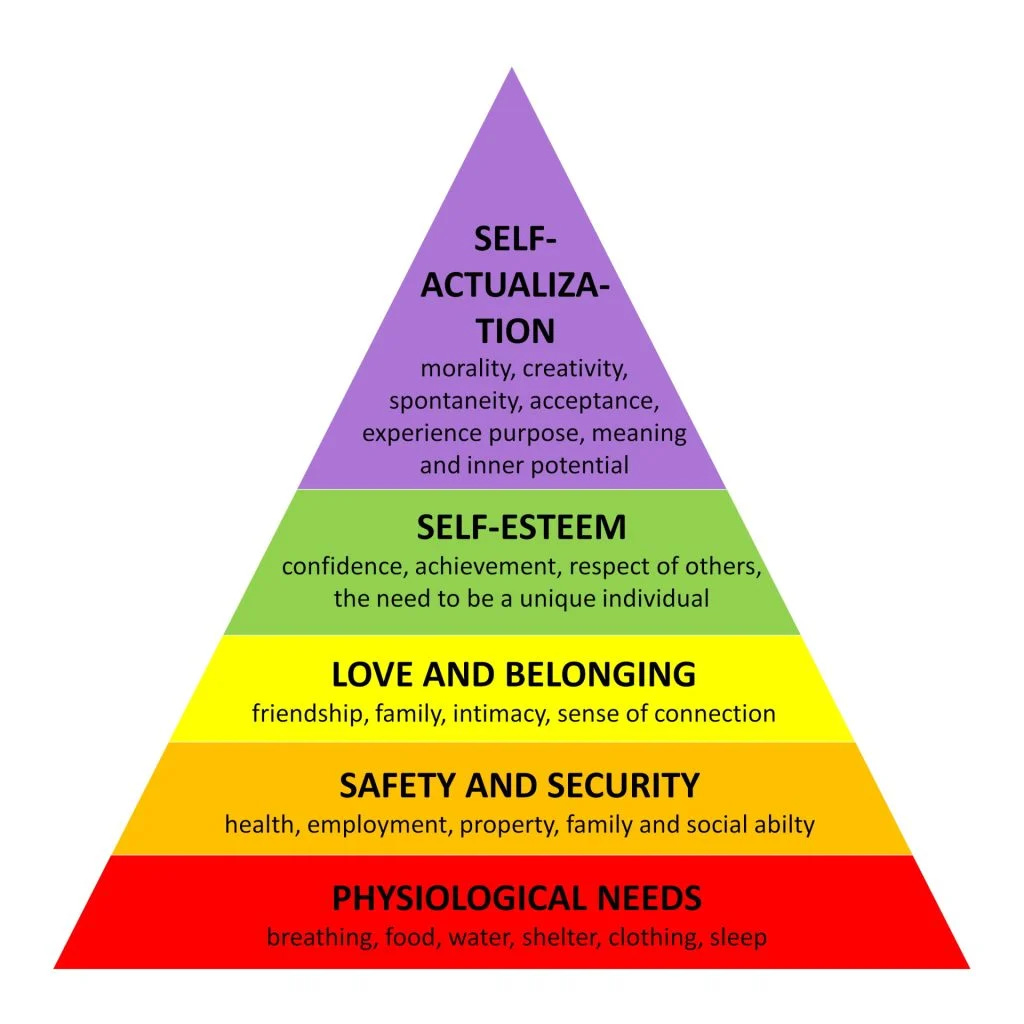

“Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs got it wrong”.

I was chatting with my friends Michael and Simon. Ok so they aren’t actually my friends. And I wasn’t really chatting with them.

I was driving, and listening to a podcast (what else is new).

They were on the podcast.

“Maslow put food and shelter at 1 and relationships at 3”, Simon Sinek insisted.

I turned up the volume. Car rides have always been where I think best. Well, that and when running. Today was a car ride.

Maslow only accounts for individuals, not groups.

The smeared colors of the New England fall landscape scurried by steadily as I meandered north on 91.

Michael Gervais, a sports psychologist and the host of the Finding Mastery podcast, chuckled as Simon processed in real-time.

“He’s only half right. If you only think of us as individuals, food and shelter absolutely come first, belonging comes later, with self actualization at the top”.

A former boss once gifted me a copy of Simon’s book Leaders Eat Last. I’ve since worked my way through his others and have heard him speak on a variety of business topics over the years.

I’d never heard him share these thoughts.

Sure, I’d heard him tackle the concept of creating workplace trust before. But directly untangling the responsibility of individual needs from team contribution was new and different.

Simon continued, “The problem is we’re also members of groups. Which means, in a community scenario, belonging comes first”.

He rounded out his freshly formed thoughts on Maslow’s misstep, “Food and shelter is probably number 3, and at the top is shared actualization. Which is how we find purpose at work”.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Unobstructed to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.